(by Diana Bird – Victoria Stilwell’s “Positively”)

Newbie dog owners and people struggling with dog behavior problems – I feel for you! The huge amount of training/ behavior information online is overwhelming and confusing. Tempting promises of quick fixes; careful use of language around every tool – kind/ gentle/ humane… What can you believe? Who can you believe?

If I was starting my dog training days now, I think I would feel quite lost.

Perhaps this is why people adopt gurus. I have misgivings about that and have written more here, but I understand that when you find someone whose work makes sense to you, it’s quite a relief.

One of my concerns with online training information is that it’s often presented as a simple recipe which you can easily follow to make a difference quickly. Most of the time I don’t think that’s true.

Think about this:

To stop smoking – don’t put a cigarette in your mouth.

To lose weight – eat less fatty and sugary food. Eat more fresh fruit, leafy vegetables and lean meat. Exercise regularly.

You see, it’s quite simple. Yet anyone who’s ever tried to do these things will tell you it’s not EASY!

Simple dog training recipes are no different. Their simplicity is attractive because we all want to achieve a lot in a short time, but they aren’t easy to implement successfully. Why not? Because of all the important detail which has to be missed out in order to keep the plan simple.

“No plan survives contact with the audience.”

You and your dog are not programmable robots. Neither of you are likely to follow a list of instructions perfectly, so you should expect training to go amiss. What’s more, because the instructions are usually incomplete (to keep them simple) you might have no idea that you need to do more. You might think your dog is now fully trained or socialized, or you might realize that he isn’t, but not know what to do next.

Even if you do follow the instructions with some success, they’re often not very effective anyway. Heck, show me a dog who learns that because you eat first or exit the house first, he should walk nicely on a leash! Perhaps they’re out there, but I’ve never met one.

I really don’t like the word ‘easy’ as an intended motivator.

It might work for some people, but I don’t like what I see when people don’t find it easy. They feel demoralized. They give up. They blame their ‘dumb’ or ‘stubborn’ dog or their ‘dumb’ or ‘inadequate’ selves. That’s so sad and so unnecessary.

Training effectiveness depends on training regularly, consistently, communicating clearly, reflecting and adapting what you do … and that depends on you, your knowledge, your skills, the people you live with, your dog, how everyone feels today etc.

Even the best instruction list can’t cover every training possibility you will face.

You just have to:

1. Train.

2. Observe the results.

3. Analyze what happened.

4. Reflect, make some changes, and try again.

5. If you are completely lost, don’t just give up. Try to find out what you don’t know. Seek help EARLY.

(And I know that simple list has a lot of gaps in it! Aaargh!)

Some dogs just absorb the rules and routines of their home with very little effort from their owner. These dogs are usually quiet, sociable and sensitive to their people. They may not be very well ‘trained’ (don’t do a lot of behaviors on cue), but they are friendly and well behaved and their people enjoy them. Other dogs need a little more input from their people to learn to be ‘well behaved’ or ‘somewhat trained’, but they get there without too much drama.

Most dogs need lots and lots of input from their people.

Some marketers encourage businesses to sell tools and ideas because when people have those, they think they have the answers to their problems. Frankly that bothers me.

Buyers might believe that all they need is a tool or a recipe to build a relationship or solve a complex issue with their dog, but it’s never going to be my sales pitch. Mine is the complete opposite, in the hope I will attract the people I really want to work with.

I want my people to know that:

YOU WILL HAVE TO DO SOME WORK!

IT WILL PROBABLY BE QUITE DIFFICULT!

YOU WILL MAKE MISTAKES!

IT WILL DO YOU GOOD!

REMEMBER YOU HAVE A SENSE OF HUMOUR!

I want people to learn to ENJOY THE PROCESS … Be willing to struggle. Be willing to problem solve. Be patient. Forgive yourself and the dog. If the dog isn’t learning it’s probably because your teaching sucks. That’s okay. You’re a learner too. Relax your shoulders. Unclench your teeth. Take a breath. Chuckle. Then play with your pup. Remind yourself that it’s only a game and you’re both learning the rules.

I study and practice this stuff yet sometimes my teaching sucks too. Then I relax/ breathe/ chuckle/ play and try again!

Here’s a little story about that.

I bought a puppy earlier this year. My older dog was a well trained 9 year old and I knew having a puppy would be hard, but it was even harder than I expected. For a start the older dog isn’t sociable. I was prepared for this to be difficult, but the reality was worse. These two spent the first 3 months separated by baby gates and closed doors. The pup wanted to be friends. The older dog didn’t. Keeping them apart, but able to see each other and interact safely was a simple idea, but it wasn’t easy. My husband and I regularly crashed into and fell over the baby gates, and had to be strategic about which dog was in the front yard, which one was in the back yard and how we would get them there. It was a darned nuisance – BUT IT WORKED! Now the dogs are great together.

My puppy bit like a piranha, didn’t like to be handled and when confused or frustrated barked or bit some more. (No, I didn’t know this when I bought her – she seemed sweet and her parents were delightful.) She screamed in the car. She didn’t want to eat what I offered her. At times I felt completely lost, missed my quiet single dog days, wondered why I had bought a puppy and what on earth I was going to do next. I was supposed to be a dog trainer and I was struggling! How did pet people survive this??

An exhausted parent wrestling with a colicky baby loves to hear from other parents about their difficulties. I was equally grateful to hear other experienced trainers share their stories of awful puppy behavior! It gave me hope and made me feel less alone and inadequate!

The most worrying problem was the biting. However, having had students with persistent biters who eventually improved, I held out hope. ( I also got a real taste of what those poor people had been up against. Not fun )

I persevered. At times I felt distressed, frustrated and angry, as well as sore and bleeding! I knew it wasn’t only that I had a difficult puppy, I wasn’t doing things clearly enough for her. I began to make my way through the alphabet with different strategies because plan A, B and C weren’t enough.

I owned the problems and adapted my training – sometimes successfully, sometimes not. I lowered my expectations. Instead of trying to work on everything at once (which felt quite overwhelming) I focused on a few things for a while, then a few different things, then a mix of both.

Why am I admitting this?

I wanted to share my struggles, so you’d realize that those simple puppy training recipes sell you a start point and no more. It’s okay to find puppy raising difficult.

I also want to share the positives. Even as a baby, Spring was responsive, and progressed quickly in many ways. This encouraged me, and let me know we were headed in the right direction despite the numerous detours and U-turns. You must NOTICE the positives! They’re very important! Focusing on negatives is easy, but they can cloud our judgement, and become all that we see. Finding positives can be hard, yet achievements are what give us confidence and motivate us to continue.

This puppy reminded me that to progress quickly, sometimes you have to slow everything down – a lot. If you haven’t heard of the 1% principle, it’s time you did. 1% daily improvement adds up to a whole lot over time. (Read more here.) Occasional big training sessions are not going to be nearly as useful as the many small sessions and interactions you have with your dog each day. Use that time well. Pay attention to how things are going, tweak your training and strive to make tiny improvements. Small things accumulate to make a big difference, not just in dog training, but in life.

Also remember that If you make a mess of a ‘big’ session, it may have a bigger impact than a messed up micro session. 3 successful brushes with a brush each day are far better than trying to do a full groom and having a major battle. If you try for a 4th brush and the dog doesn’t like it – you just learned that’s too many for now (messed up micro session – no battle.)

At eleven months old, I thoroughly enjoy my little border collie. Her behavior has been a steep learning curve, which I always knew I would appreciate – and now (thankfully) I do! Raising her has been hard work and the work continues, but it has also been well worth the effort. She’s teaching me a lot, is great to live with and I love her.

I leave you with these reminders.

A lot of simple things are not easy (and that’s okay.)

Training plans and recipes are just starting points, not magic spells.

No plan survives contact with an audience. Expect to make many adjustments.

Be ready, willing and able to spend time with, and work hard for your puppies.

Use the 1% principle to develop and learn from the process.

(Take advantage of the learning and apply the 1% principle to other parts of your life.)

Your hard work will be rewarded with a thoroughly enjoyable canine companion!

Good luck and enjoy!

https://positively.com/contributors/no-plan-survives-contact-with-reality/

Post Date

January 21, 2016

games you can play in your living room.These games add in the fun, take off the pressure and teach key skills!

games you can play in your living room.These games add in the fun, take off the pressure and teach key skills!

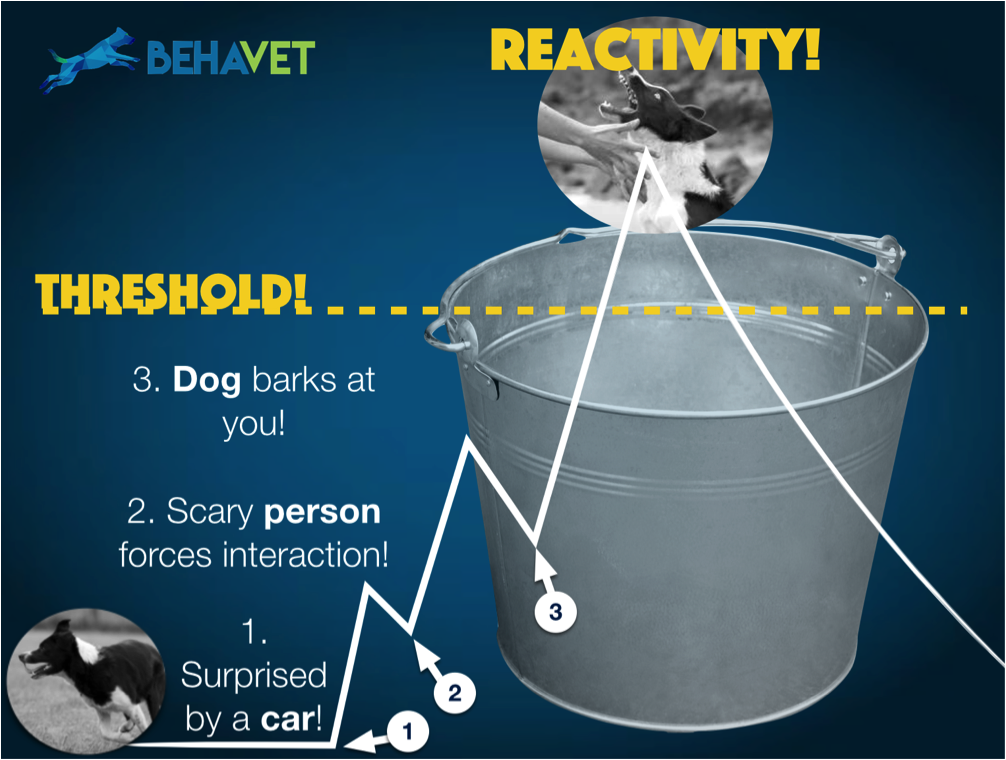

cumulative and doesn’t go down quickly! The best analogy to look at this is that of an “arousal

cumulative and doesn’t go down quickly! The best analogy to look at this is that of an “arousal An awareness of this concept is crucial in both companion and performance dog training as well as working with Naughty But Nice dogs:

An awareness of this concept is crucial in both companion and performance dog training as well as working with Naughty But Nice dogs: